By the Historic Preservation Committee – North Shore Chamber of Commerce

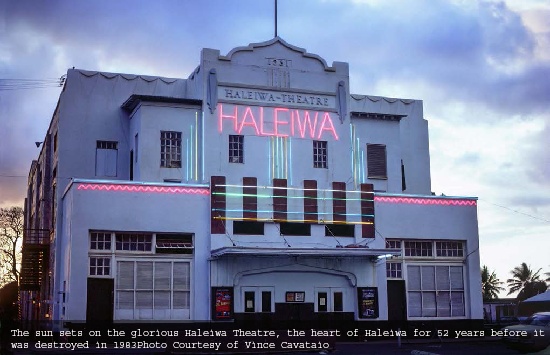

One of the most magnificent buildings ever constructed in Haleiwa, the Haleiwa Theatre was a classic example of much more than just its unique art deco style. It was also a classic symbol of what was done right and what could go wrong.

The structure was designed by Hego Fuchino who left Japan for Hawaii as a teenager and rose to become one of Hawaii’s first and finest Japanese architects. To bring Fuchino’s drawings to life, massive boulders in Kemoo Hills Plantation were quarried and expertly cut into twelve-inch blocks by a stonecutter from Japan. George Tanabe, the younger brother of the building’s contractor Walter Tanabe, helped to haul the stones to Haleiwa. He later recalled how it took two years to accumulate enough blocks to complete construction of the theatre. The lava rock foundation was finished with a concrete face with multipaned windows and store fronts on either side of the entrance.

Designed as a venue for live performances with an orchestra pit in front of the stage and a trap door to dressing rooms below, the theatre could accommodate 900 people with seats on the main floor and cushioned seats in the balconies. A balcony on one side of the stage was called the Queen’s Box in memory of Queen Liliuokalani. The theatre was the epicenter of entertainment for the North Shore community for half a century where families enjoyed vaudeville productions, Japanese plays, Filipino shows, Hollywood movies, concerts, and other events, bringing a touch of class and levity to plantation life.

A smaller theatre known as the Eiraku or Konno Theatre had operated on the site for twenty years previously. Haleiwa’s Shimoda family resided on the third floor above the second story theatre and ran a store on the street level. They later ran the concession in the Haleiwa Theatre into the 1940s. Tomitaro Konno, the owner of the Eiraku, led a small group of investors to form the Haleiwa Theatre Company which acquired a lease on the land under the Eiraku, making way for a more modern theatre. The Haleiwa Theatre officially opened on December 15, 1931, with Konno serving as the General Manager, a position he held for decades.

The Haleiwa Theatre provided entertainment for fifty memorable years before the final curtain dropped. Trouble began with a slowdown in the movie business before shows were discontinued altogether in 1978. Then there was the impending expiration of the 50-year lease of the land under the theatre. In 1979, developer Lee Martin stepped into the picture and bought the property on an agreement of sale months before the lease expired in February of 1980. Konno and the Haleiwa Theatre Company filed for dissolution three months later.

Martin had promised to renovate the building but refused to fund any substantial repairs. The future of the theatre hung in the precarious balance between preservation and progress. With a promise that the profits would go into the remodeling of the theatre, Martin received the Neighborhood Board’s approval to sell a portion of the land to the Southland Corporation. Instead, he applied for and received a demolition permit from the city. In the early morning of September 9, 1983, a demolition crew shocked the community as the historic structure began falling to the wrecking ball. Armed with a demolition permit issued in error, Martin and his crew ignored city officials’ demands to stop the devastation.

Despite protections already on the books under interim development controls enacted by the City Council in 1982, the theatre was irreparably damaged due to a “procedural error” by a clerk within the Building Department unaware of a specific rule. Admitting the mistake, City officials obtained a restraining order the next day. In and out of court for the next few weeks, previously undisclosed details of the path to destruction came to light.

Determined to expose the injustice of the developer responsible for the damage, Hawaiian Airlines pilot Rick Rogers took flight. From his perch atop the rubble of the theatre, in court hearings and public meetings, Captain Haleiwa as he famously became known, insisted that the demolition permit was never properly issued and the developer needed to be held accountable. The matter was ultimately decided by a citizen panel. With no explanation for its decision, the Building Board of Appeals voted to approve the demolition, sealing the fate of the Haleiwa Theatre. On November 7, 1983, the cornerstone of the Haleiwa Special Design District was destroyed.

From the Haleiwa Special District Design Guidelines established in 1991, to the establishment of the Haleiwa Historic, Cultural and Scenic District in 1984, amended as recently as 2018, the goal has been to preserve and enhance the rural character of Haleiwa going forward. Preventing the demolition of a historic structure on private property is another matter. Had the law in existence at the time been followed and Martin’s application for a demolition permit been routed for proper review by the Department of

Land Utilization as required, could the theatre have been saved? We will never know, but the legacy of the Haleiwa Theatre and the valiant effort to save it from destruction sparked a movement to ensure the same bureaucratic mistake will never happen again.