By Boyd Ready

We all understand that for the country to stay ‘country,’ we need agriculture. To provide food and fiber our farmers need land, water, capital investment, and labor. Let’s focus on water.

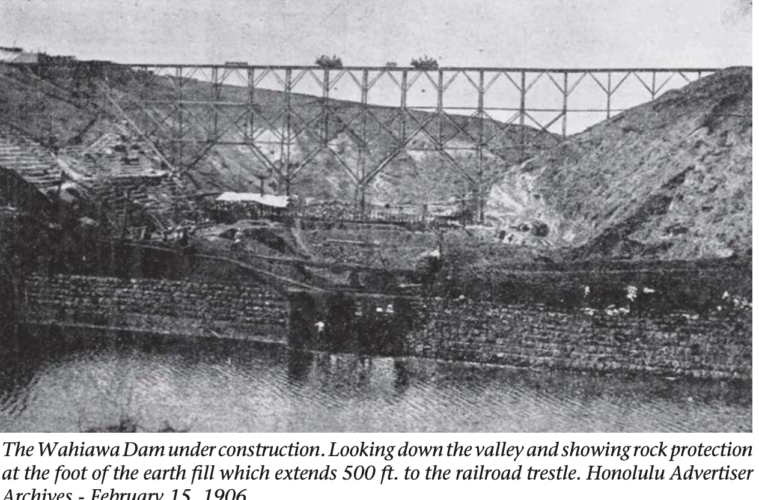

Lake Wilson was created by the early Waialua Sugar Company with water from the upper reaches of the Kaukonahua Stream, fed by Ko‘olau Moun- tain streams on either side of what is now Wahiawa town. Around the same time as the construction of the Panama Canal, from 1902 to 1905 thousands of Japanese and Korean laborers, donkeys, wheelbar- rows, dynamite and mining-train tracks excavated 30 horizontal tunnel shafts to add steady, groundwater flows into the streams. They then built a massive earthen dam using a rail trestle over the canyon. They dropped giant rocks and loads of earth from above, compacting it, then topping it off with rip- rap (dry-laid stone used to form a foundation). This reservoir can hold almost 3 billion gallons of water for controlled release.

Ancient Hawaiians had long mastered the art of directing the gravity flow of water. In fact, Waialua’s people built a two-mile long stone-lined ditch by hand, reputed to be the longest ancient Hawaiian water ditch. It brought water from Kaukonahua Stream, near Mt. Ka‘ala, down to kuleana farm plots in what is now Waialua town. The early Waialua Sugar operations used that same ditch until

replacing it later with ‘Pump 1,’ above Waialua town, for a more reliable groundwater flow.

Ancient Hawaiians in Waialua also used the fresh- water spring-fed and moun- tain stream-fed wetlands for taro fields that supplied a population of 8,000 with the staple, and sacred, food: poi. Combined with sweet potato, nearshore fisheries, bread- fruit, pig, dog, and chicken, and the famous Loko ea and other aquaculture ponds, Waialua was ‘aina momona, a fat land, well-watered and so, waiwai, wealthy.

Waialua suffered a huge population loss in the 1800s which overwhelmed traditional Hawaiian agriculture. The population fell from 8,000 to a low of 1,200 due to epidemics and emigration. As it re- bounded, kalo fields in our low, spring-fed wetlands on the makai side of Hale‘iwa, transitioned to rice production primarily by Chinese immigrants. Waialua was Oahu’s second largest rice producer in the 1870s.

Later, when Japanese immigrants preferred im- ported California rice, the wetlands transitioned to lotus, or ‘hasu’ plantings, a staple in the Japanese diet. Many of these areas are not farmed today perhaps due to the hard, manual labor needed for this kind of farming. However, there are some farmers who grow kalo profitably in these same wetlands today. But our vast uplands between Wahiawa and Hale‘iwa need reliable water from Lake Wilson flowing by gravity.

By comparison, our Board of Water (BWS) provides Waialua and Hale‘iwa about 2 million gallons per day for domestic and agricultural used. BWS potable water costs too much for many crops because of the electricity it takes to pump the water from the ground. The Waialua Sugar Co. water system provided over 60 million gallons per day mostly from the Ko‘olau watershed, the 30 hand-dug collection tunnels and Lake Wilson, therefore not needing electricity for pumping.

Lake Wilson has an earthen dam with an im- proved, enlarged spillway for safety, and is the largest freshwater reservoir in the State. Its five outlet valves have been repaired, and substantial parts of the open ditch distribution system have been retrofitted to pip- ing. The Hawaii State legislature is now considering buying Lake Wilson from Dole Food Company. There is no water shortage for the North Shore, but it needs Lake Wilson for its low cost, gravity-fed water and flood-control features. With surface water like this we can support our farmers and agriculture growers to “keep the country country.”